The French left’s surprise victory in their recent snap legislative elections offers rich lessons for socialists in the US. With right-wing authoritarianism rising both domestically and internationally, France offers us both a cautionary warning of the existential threat posed by the fascist right as well as an inspiring example of what must be done to defeat them.

However, US socialists have struggled to interpret the French left’s success, with some arguing it proves left and progressive forces must put aside our differences with centrist Democrats in order to unite and fight the right, while others argue that it implies the exact opposite, namely that socialists must “break with the Dems” in order to build an independent party of the left. Ironically, the New Popular Front—so successful at overcoming the historic fragmentation of the French left—has sparked debates among US socialists that seem only to further entrench deep divisions here.

So does the New Popular Front teach us that we must build an uncompromising left, or that we must compromise with centrist forces inside a broad anti-fascist front? Actually, both! As I will argue, the French elections demonstrate that we must learn to walk and chew gum at the same time—strategically uniting the left while tactically coordinating with centrist forces to defeat the rising fascist threat. On both aspects of this two-pronged strategy, the French example has much to teach us.

A rising right and a crumbling center

Less than a month ago, France risked finding itself under fascist rule for the first time since the Nazi era. This is not hyperbole: the party then polling in first place originated as the public, electoral wing of an underground neo-fascist movement explicitly inspired by the European dictatorships of the 1930s. Once known as the National Front, it has since tried to rebrand itself as the Rassemblement National or “National Rally” (RN). Make no mistake, however: beneath the rebrand it remains an extremist, ethnic nationalist and authoritarian movement—new clothes, same wolf.

In the European parliamentary elections of early June, the RN and another far-right party together received almost 40 percent of the vote—their highest-ever total—in a rebuke to centrist President Emmanuel Macron and his deeply unpopular austerity measures, neoliberal policies, and undemocratic practices. Because the EU parliament possesses much less power than its component states, this far-right win, while deeply alarming, was in part symbolic. But Macron’s response to this electoral rout was even more shocking. Faced with a symbolic defeat, he decided to risk a real one, dissolving the National Assembly and declaring snap legislative elections on barely three weeks' notice.

This rash decision (announced without apparent consultation with his party or advisors) seemed based on a risky bet that he could “call the bluff” on an angry French public—holding a metaphorical gun to their heads and demanding they vote for him to forestall the fascist threat. If that was Macron’s cynical gamble, it immediately backfired: as the three-week clock ticked down, his party’s popularity only sank further. Meanwhile, the far right’s star rose higher and higher, with polls suggesting they would not just win the largest vote share in a pluralistic legislature, but might actually secure an outright majority. For the first time since the collaborationist Vichy regime of the 1940s, it seemed France might soon find itself waking up to a fascist prime minister, a fascist parliament, and a fascist government.

In the face of neo-fascism, a New Popular Front

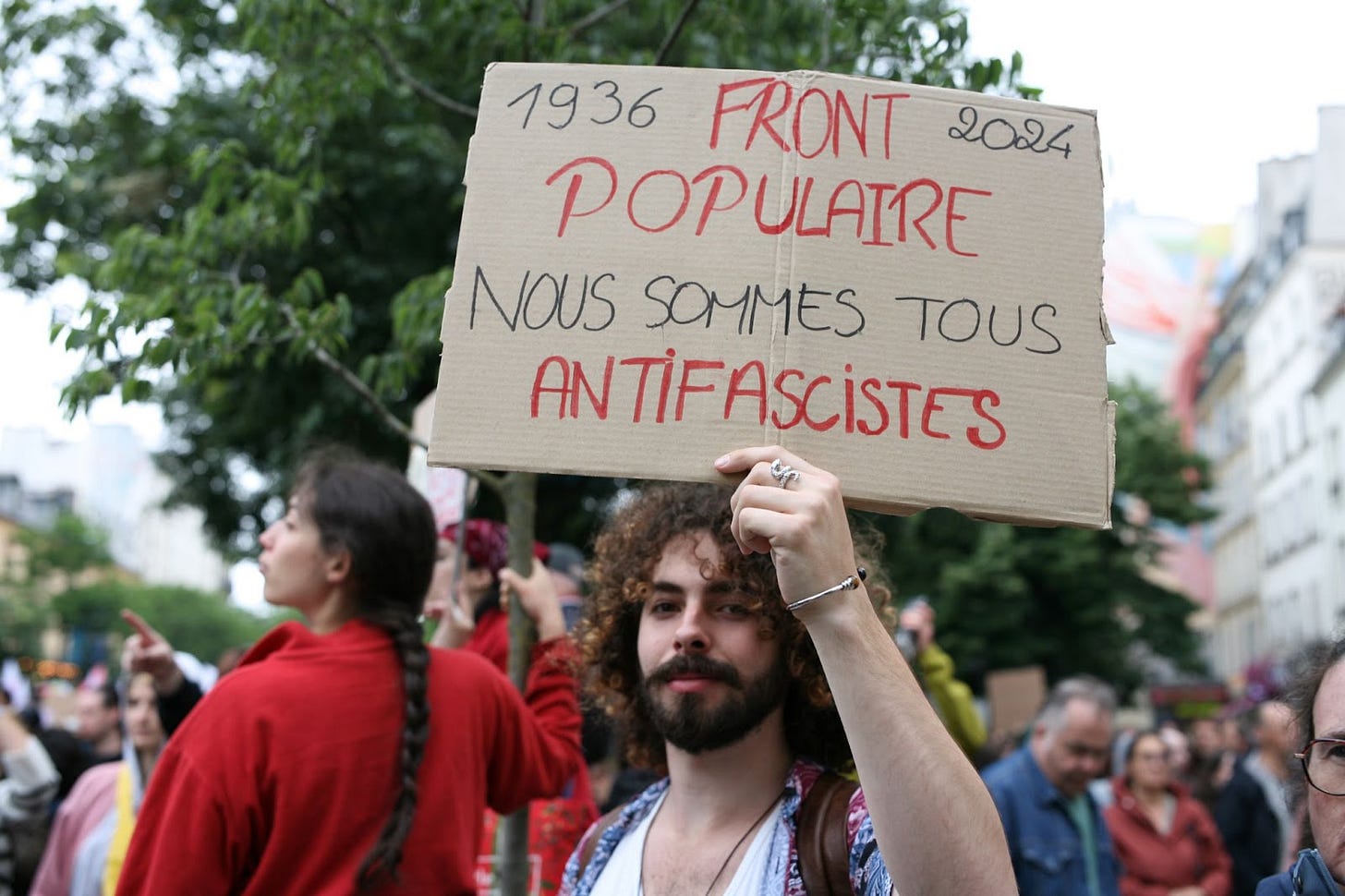

Instead, it was the left that rose up—rousting to confront the historic threat with levels of mass mobilization and political unity virtually unprecedented in recent French history. Within days, hundreds of thousands of people had taken to the streets, calling on all forces opposed to fascism to put aside their differences and unite to fight the right. Heeding this call, the parties of the deeply fragmented French left overcame old divisions and rapidly hammered out a coalition agreement and a shared platform in order to present a common slate of candidates to oppose the fascist front. Recognizing the unprecedented nature of the political moment, hundreds of NGOs, labor unions, and civil society organizations broke with a longstanding tradition of political non-partisanship and endorsed the coalition, calling on their members to join the fight against fascist forces.

This unprecedented coordination of social movements, civil society, and the party left—what sociologist Clément Petitjean has called a “convergence of unity from above and mobilization from below”—quickly assumed the name of the Nouvelle Front Populaire (NFP) or New Popular Front. The term gestures back to the “original” Popular Front of the 1930s, which likewise united the forces of the French Communist, Socialist, and center-left with organized labor and civil society organizations to combat a growing fascist movement that threatened to topple the French republic. This “OG” Popular Front went on to win the legislative elections of 1936, elected France’s first Jewish prime minister, passed major economic and social welfare legislation, and successfully contained the fascist threat, at least until the Nazis conquered France in 1940.

In adopting this historic legacy, the New Popular Front thus correctly recognized both the extremity of the far-right threat and the urgency of the left’s historic task: to construct a front broad and deep enough to successfully combat resurgent fascism.

This would have been no small task under any circumstances, but the snap elections required them to build this anti-fascist front in a mere three weeks! Not only that, but the left had to navigate the complexities of building not just one front, but two—a “Popular Front” uniting the parties of the left as well as a broader “Republican Front” involving tactical coordination with the center and center-right. As we will see, this dual strategy was key to securing a left victory and preventing fascist forces from seizing power.

A two-round electoral system and a two-pronged strategy

To grasp the left’s two-pronged approach to front-building, we must first understand France’s two-round voting system, which combines political pluralism with a “winner takes all,” first-past-the-post model. In the first round, all parties who choose to field candidates for any given legislative district appear on the ballot. Should any of these candidates win an absolute majority (50 percent plus one), they are the winner, and the election in that district stops there.

Should no candidate receive a majority, the top two proceed to a run-off election that takes place just a single week later. In addition, however, any other candidates who garnered at least 12.5 percent of the registered vote also continue to this second round. This means that in some cases run-off elections can involve three or even four candidates. And critically, in this second round whoever receives the most votes wins, regardless of whether or not they exceed the 50 percent mark.

This is significant because, while fascist forces are growing in France, they are by no means a majority. The 40 percent of the vote they received in the EU elections is both their highest-ever total and, for now at least, likely their ceiling of support. Because of this, in most districts, the combined anti-fascist vote is large enough to defeat the far right—in a two-way race. In a three- or four-way race, however, multiple candidates and parties risk splitting the anti-fascist vote, handing the far right a win.

In recent years, this has led many parties to tactically withdraw their candidates from second-round legislative elections in contexts where they might split the anti-fascist vote. This tactic has often been called the “Republican Front”—a term that refers, not to France’s right-wing Republican party, but to the norms and values of the French system of government, the Fifth Republic.1

The French left’s electoral intervention thus involved a two-pronged strategy, corresponding to the two rounds of the legislative elections, and necessitating two different fronts. The first, “Popular” Front was based on a strategic alliance among the major parties of the French left. The second, “Republican” Front broadened out from this socialist core to include tactical coordination with centrist and center-right forces. Let’s examine these two aspects in turn.

A Popular Front to build the left

The Popular Front component of this two-pronged strategy entailed building unity with other left forces in order to run a common slate of candidates. Concretely, this meant that the coalition divided up parliamentary districts among its constituent parties, based on their overall size and strength as well as on context-specific calculations as to which of them was best positioned to win in particular districts. While described as a common “slate,” the candidates remained affiliated with the individual parties participating within the coalition, and were listed as such on the ballot. The figure below shows the division of constituencies among the 4 major parties participating in the NFP: the far-left La France Insoumise (shown in dark pink) the French Communist Party (red), the Ecologists (green), and the more moderate Socialists (light pink).

Simultaneously, the parties hammered out the details of a common platform which, in contrast to the typical vague platitudes of most party programs, presented a compelling governing agenda, at once concrete and visionary, and broken down into three phases. In the first, the NFP promised to pass immediate “emergency” measures, including a minimum wage increase and price controls on staple goods and utilities, to provide the working classes with rapid economic relief. Second, they pledged to pass five legislative packages in their first hundred days in office to provide a deeper “change of course” on education, health care, the environment, purchasing power, and tax policy. These legislative packages would in turn pave the way for structural “transformations” intended to fundamentally shift the balance of power away from the wealthy few towards bottom-up political and economic democratization, culminating in a proposal to convene a citizens’ constituent assembly to rewrite the constitution and create a new Sixth Republic.

This three-part program created a bridge from immediate measures to stepping stone reforms to major structural transformation. Attacked by Macronists as “delirious” and “unrealistic,” the platform in fact outlined a quite realistic and practicable plan to fundamentally restructure political reality. This allowed the NFP to present a clear, cohesive and compelling alternative to both the threat of fascism and the manifest failures of neoliberalism. In effect, what they proposed was a whole new mode of politics, or what some left theorists have started calling a new governing paradigm—”the dominant political framework of a given era that structures the ‘common sense’ of how government, the economy and society operate.”

Thus, the first, “popular” phase of anti-fascist front-building involved cohering a left core who could provide a compelling alternative to both the far right and the neoliberal center. Eschewing the factionalism that had long plagued the French left, the participating parties employed a collaborative model that allowed them to present a common platform and a single list of candidates while maintaining organizational independence and a degree of autonomy. (The NFP was not a formal party merger, in other words, but something more like a federation.)

A Republican Front to defeat the right

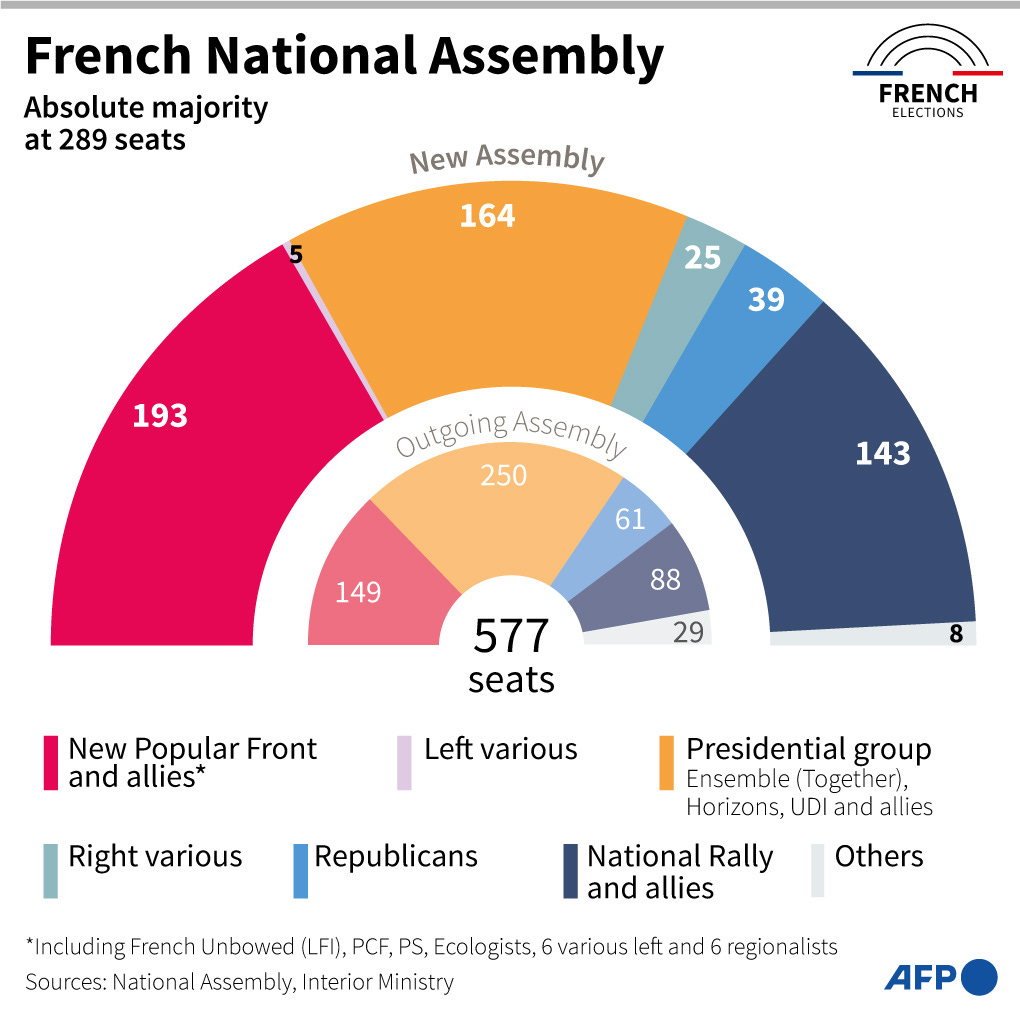

In the first round, this Popular Front strategy allowed the combined parties of the NFP to secure a first-place result in 156 districts, of which 32 races were won outright. This was a strong showing, putting the coalition well ahead of Macron’s centrist Ensemble grouping. However, the NFP still ended up more than five points behind the far right, which won 37 seats outright, and secured a first-place finish in 296 districts—almost double the total of the left. And with the electorate deeply divided between the far-right RN, the center-right Republicans, the centrist Ensemble, and the NFP, a record 311 races were slated for a three- or four-way runoff, threatening to hand the RN a blowout win. With France’s anti-fascist majority divided among multiple parties, the far right was still on the ascendant.

So just as critical as the left’s first-round strategy was what they did next. To forestall a far-right victory, the NFP invoked a broader anti-fascist Republican Front involving tactical coordination with the center and center-right. In cases where they had secured one of the top two positions in the first round of voting, the NFP called on the centrist and center-right parties to withdraw their candidates and throw their weight behind the left. In all those races where they had finished third or fourth, meanwhile, the NFP announced that they would immediately withdraw their candidates and urge their supporters to vote for the center or center-right. In doing so, they made clear that they retained serious political disagreements with centrist and center-right forces; this was not a deep strategic alliance, but rather a temporary and tactical truce between competing blocs who remained at odds, but who were simply not strong enough on their own to defeat a shared existential threat.

It was the principled, united, and consistent stance of the NFP around this second and broader Republican Front that prevented a fascist victory in the second round. Infuriatingly (if predictably) the centrist and center-right parties did not immediately do the same. The Republicans initially refused to issue any official instructions to their candidates at all, while Macron announced that his party would tactically coordinate with Socialist, Communist, and Green candidates, but not with the far-left LFI, whom he claimed represented a threat to the “values of the Republic” equivalent to that of the FN. In the face of these potential fractures, the NFP retained remarkable unity inside the Popular Front, while remaining equally adamant that the left, center, and center-right must tactically coordinate in a broader Republican Front to defeat the RN. Ultimately, their example compelled all but 12 Republican candidates and 15 Ensemble candidates to withdraw from three- and four-way races that they threatened to spoil, forestalling a far-right win.

The NFP thus applied a two-pronged approach, uniting the left in a single, consolidated bloc, while also playing a leading role in cohering a broader anti-fascist coalition involving left and center, and even much of the center-right. This two-pronged strategy allowed the left both to articulate a compelling vision for millions of voters rightly disillusioned by the failures of the neoliberal center, and to coordinate with centrist forces in a context where neither left nor center had the ability to defeat fascist forces on their own. It was the combination of this two-pronged, both/and process that allowed the NFP to emerge as the shock winners of the second round of the elections—not only helping defeat the right, but securing the largest number of seats in the new parliament, though still short of an absolute majority.

The French left’s unity inflames divides among US socialists

Understandably, the French left’s achievement electrified socialists in the US and globally. More accustomed to defeat than victory, we suddenly had a rare example of an inspiring win! And for US leftists in particular, the parallels felt uncanny, as we too found ourselves facing an upcoming election between an uninspiring centrist president and a far-right MAGA movement threatening to replace a flagging neoliberalism with something even worse.

But if the French example offered us a lesson, US socialists almost immediately disagreed about what it meant. Some argued that it showed the need to build the broadest possible anti-fascist front in order to defeat Trump and MAGA in November. Others countered that, to the contrary, it proved the need for a decisive break with the Democrats in order to build a fully independent left. The NFP clearly offered us a lesson… but which one?

Some of this confusion is no doubt due to the differences between the French and American election systems. Among other things, the peculiarities of the US electoral system effectively preclude running winning candidates on an independent ballot line—the exact tactic the NFP used so successfully. So how to “translate” the French lesson to a US context?

Translating French electoral strategy to US conditions

In fact, this task is not as complex as it might seem, because the French and US election systems—while highly anomalous when compared to more widespread parliamentary models—actually resemble each other more closely than they appear. Just read the following paragraph and try and guess whether it describes the French or American model:

This country elects politicians through a two-round system. In the first round, multiple candidates appear on the ballot—potentially a large number. In the second, the top vote-getters from the first round are pitted against each-other in a head-to-head contest. While sometimes more than two names appear on the ballot, candidates beyond the top two have almost no chance of winning, and are widely regarded as spoilers. This incentivizes diverse political interests to coalesce behind two candidates.

So is this a description of US or French politics? It’s a trick question, of course—the answer is both! That’s because US primaries roughly correspond, as their name would suggest, to the first round of French legislative elections, and US general elections to the second. There are of course significant differences. But at a high level of generality, both France and America have dual-election systems in which the first round involves multiple candidates representing very different factions and forces, while in the second these factions are structurally compelled to coalesce into broad, uneasy coalitions behind the top two candidates.

The Republicans and Democrats not as parties, but fronts

In other words, the Democratic and Republican coalitions are themselves broad-tent coalitions, analogous to the tactical alliances that come together in the second round of French legislative elections. Just as in France, this produces strange and uneasy bedfellows: Bernie Sanders and Kirsten Sinema have little more in common than do the far-left firebrand Jean-Luc Mélenchon and the neoliberal Macron. Nevertheless, the binary logic of the electoral and political system at times propels these political rivals into tactical, temporary, and unstable compromises against common enemies, even as they continue to disagree bitterly with one another.

These parallels are obscured by the fact that in France such uneasy alliances of convenience are formed between formally independent parties, while in the US they appear to occur inside the same one. Again however, these differences are less than they might seem. That’s because, as others have noted, US political “parties” are not really parties at all, in the sense of stable organizations with a bounded membership that determines organizational policy, selects internal leadership and chooses which candidates to run for office. In the US, the parties’ choice of candidates is instead determined by a public process controlled and administered by the state, while their “membership'' is little more than a checkbox on a government form. In many ways, they are more like “quasi-public entities akin to public utilities”2 around which various private interest groups coalesce and compete.

Possessing neither a binding platform nor bounded membership, the Democrats and Republicans are thus less parties than “constantly changing coalitions with no firm commitment to program or discipline,” as Carl Davidson puts it. Within these loose and shifting alliances, we can identify relatively coherent factional interest groups, our closest analogue to French political parties in the sense of internally organized networks of organizations and individuals with a shared political program. However, these factional blocs are multifarious—Davidson identifies six.

Depending how you parse it, then, the United States either has no political parties, or many of them. Thus, many debates on the US left about the Democratic Party commit a sort of category mistake. When we ask “how should we relate to the Democratic Party?” the question is not how to relate to a coherent entity with a stable leadership and a shared political program. Rather it is: how do we relate to this loose, unstable and shifting coalition, inside of which various factions and forces alternatively contest and cooperate? In this sense, the Democrats and Republicans are best understood not as parties but fronts, and any form of engagement with(in) them as itself a “frontist” politics.

Tectonic Shifts

In recent years, dramatic transformations have occurred within the political fronts in both France and the US. Previously dominant blocs have been utterly marginalized, while formerly marginal forces have risen dramatically. But the nature of the French system makes this much easier to perceive.

From the 1980s until quite recently, two fairly stable coalitions alternated power in France—one led by the center-right Republicans (and its predecessor parties) the other by the center-left Socialists. While the two contested fiercely, they largely operated within a shared governing paradigm—what one might call a “neoliberal consensus with French characteristics”—that dominated French politics from roughly 1984 to 2017, when it collapsed abruptly.

That year, for the first time, neither the Socialist nor the Republican candidate made it to the second round of the French Presidential elections. This catalyzed a sea change in French politics, with the formerly hegemonic center-left and center-right blocs cratering to single-digit support levels from which they have never recovered. In the void left by their collapse, the far-right RN rose dramatically, as did Macron’s new Ensemble coalition—which itself both partially caused and then went on to claim the power vacuum left in the political center. But Macron’s attempts to create a new technocratic governing paradigm of the “moderate middle” proved wildly unpopular, in turn creating an opening for the NFP.

A decades-long political paradigm collapsing, unprecedented new formations emerging on the far-right, left and center and vying to establish a new consensus, without any proving able to secure a stable governing majority… clearly, these are tectonic shifts. Not only would it be absurd to apply the past categories of French political analysis to this changed conjuncture, it’s in fact impossible—the parties, players and political map are all too different.

Not your father’s Republican Party

In the United States, equally huge sea changes have occurred—and on roughly the same timeframe. Yet too many—from the mainstream media to many sectors of the Socialist left—still make the mistake of treating the Republican and Democratic coalitions as if they were the same old neoliberal establishment of yesteryear. The US’s “frontist” political system makes it easier to make this mistake, since these transformations have occurred within the Republican and Democratic “parties,” rather than outside them. Make no mistake, however: on both sides of the aisle, there have been tectonic shifts.

On the right, authoritarian white Christian nationalists, who formerly existed as a junior partner in the GOP coalition, have united with formerly fringe neo-fascist elements to wrest decisive control and leadership of the GOP from the previously dominant neoliberal establishment (now scornfully rejected as “RINO” Republicans). This is equivalent to the RN’s astonishing rise, and even more alarming—for while the French Républicains have largely refused collaboration with the RN, establishment Republicans have generally fallen in line behind their American equivalent. In this sense today’s GOP has become, quite literally, a fascist front.

The balance of power within the Democratic coalition is more complex. In contrast to the total eclipse of the neoliberal Republican establishment, the centrist Democratic bloc remains dominant—but, extraordinarily, it has abandoned its commitment to neoliberalism. (While it is led by many of the same players as the 1990s “Third Way” Democrats, it no longer has the same politics.)2 Meanwhile, the left-wing, social-democratic faction has undeniably strengthened, illustrated among other things by the increasing size and internal cohesion of the Congressional Progressive Caucus. At the same time, the flight of some moderate GOP voters from the radicalized fascist front has exerted a countervailing rightwing pull.

In effect, the Democratic coalition has become the electoral expression of a broad anti-fascist alliance, one that both contains an emboldened and increasingly coherent left bloc but also unites a quite wide range of competing interests and divergent viewpoints on the center and even center-right. At the risk of confusion, the Democratic Party is thus itself the equivalent of the French “Republican” Front, which in our context we might better call a pro-democracy front—a tactical alliance containing a wide array of divergent forces (from Noam Chomsky to Liz Cheney) who share little in common beyond their shared opposition to the far right’s authoritarian agenda.

Fighting centrists in the primary, uniting in the general

With this understanding of the US parties as coalitions, it is easier to translate the French Left’s two-pronged strategy to our conditions. Just as in France, so too the US left must find ways to build our own independent initiative, while also tactically coordinating with centrist forces in order to counter the threat posed by the MAGA right.

This both/and orientation—strategic unity with the left, tactical coordination with the center—is one that my organization, Liberation Road, has long called for, as part of an emerging inside/outside trend among US socialists. But because the Democrats and Republicans are not parties but fronts, the independent “party of the Left” that we need to build is not synonymous with our own ballot line. Instead, it looks more like what we and others have started to call independent political organizations (IPOs)— democratic membership organizations able to wage issue campaigns, run electoral organizing programs, and field candidates.

These candidates will (generally) run on the Democratic line, but with very different orientations to the primary and general election, corresponding to the two “prongs” of the French strategy—that is, to the Popular and Republican fronts.

So what does this look like in practice? The left should field our own candidates in US primary elections, running on a clear progressive platform distinct from and opposed to the neoliberal centrist establishment. In cases where more than one left or progressive candidate intends to run in the same race or district, every effort should be made to secure enough alignment to unite behind a single candidate, the choice of which should be based on calculating who stands the better chance of defeating centrist rivals. Ideally, such decisions should be made, not individually, but in relation to durable, democratic membership organizations with clear progressive politics and a mass base. This stage corresponds to the first, “popular” front component of the NFP’s strategy.

US Leftists should make every attempt to secure a victory for our candidates in primary elections. (While we should not abandon running candidates in hard-to-win races and places, our goal is to win!) If we are victorious in the primary, we must then pivot to tactically unite with the centrist forces we have just defeated in any context where we face a right-wing opponent in the general election who poses a credible threat. Beyond asking for the votes of the centrist electorate, we should seek additional forms of support from centrist political forces (donations, endorsements, etc.) without however denying our differences with the center or compromising the independence and integrity of our electoral program.

The reverse is also true. When we are defeated by centrist opponents in the primary, and face a credible possibility of a right-wing win in the general, we must tactically coordinate with the center, offering our critical support. This includes not just voting for centrist candidates and calling on our supporters to do so, but also mobilizing our own resources (financial, logistical, and other) to ensure that we defeat the MAGA right. Again, we should do this in ways that do not deny our differences with the center and preserve the integrity of our own independent electoral program. But the threat of a far-right political victory is simply too great for us to sit elections out. This corresponds to the second, “Republican” front stage of the NFP’s two-pronged strategy.

Three more French lessons for the US left

In recent years, leftists aligned with this orientation have been working to build and implement just such a two-pronged strategy. At a national level, the Working Families Party has been gaining strength and momentum. At the state level, new IPO projects like Down Home NC join longstanding formations like the Ohio Organizing Collaborative or New Virginia Majority. At the local level, countless left and progressive groups are experimenting with applying this inside/outside strategy to a municipalist model. And on the socialist left, new organizations like North Star Socialist Organization strengthen existing efforts to develop left electoral strategy, while sections of the DSA continue to secure exciting electoral wins (although internal schisms threaten to derail this momentum).

These experiments are all exciting, but they are not enough. The example of the French New Popular Front teaches us three more important lessons about what must be done to defeat the far right:

We must form a left/progressive Front in practice (not just in theory). As the NFP has shown, the left can only offer a compelling alternative to the far-right project when we put aside our differences to forge a left alliance greater than the sum of its parts. This is something that many sectors of the left have long agreed is necessary, but so far verbal commitment has not translated into deep enough changes in our organizational practice. Faced with the imminent prospect of a fascist government, the French left managed to forge a powerful new coalition in just three weeks time. What would it take for the US left to pursue this task with the same urgency?

Organized labor and nongovernment organizations must join the Front. Many sectors of organized labor purse electoral work, as do nonprofit organizations like Planned Parenthood. But beyond occasional engagement with left formations like WFP, most of them either do so independently or through coalitions typically dominated by centrist Democrats. Meanwhile many others eschew partisan politics entirely—including groups leading powerful organizing work like the Union of Southern Service Workers. In France, hundreds of nonprofits like Greenpeace and powerful unions like the CGT put aside a longstanding practice of nonpartisanship to join the NFP, recognizing that the fascist threat required a change of tactics. We must do the same. Progressive labor should pursue a strategy of political power unionism, while both unions and NGOs should join and build left electoral coalitions at the local, state, and federal level.

Our Front must build a shared platform sequencing short-term demands towards a long-term governing agenda. The NFP put forward a platform that combined immediate measures with an ambitious policy agenda focused on passing five key pieces of legislation within their first 100 days in office. Our front should do the same, coalescing around three to five transformative demands we can jointly push for in the first 100 days of a new administration. While this may seem ambitious, we should recall the example of the “original” French Popular Front, which managed to pass 133 laws in 73 days (a pace of two a day!) including nationalizing key industries; making higher education free; setting price controls on key consumer goods; creating a major public works program; and passing landmark labor legislation that legalized the right to strike, formalized collective bargaining, and established the 40-hour work week and two weeks paid vacation. We must be as bold in putting forward a shared platform to enact a new governing paradigm.

Finally, the New Popular Front teaches us that we must do the hard work of building left unity while simultaneously working with and in a broader anti-fascist front that includes centrist and even center-right forces. This does not mean we abandon our politics or our policies, nor that we endorse those of our temporary, tactical allies. But while the individualism of American political discourse often treats voting as an expression of individual values or an endorsement of individual personalities, elections are collective contests between contending social, political and economic fronts. There is no question that an electoral victory by the “Pro-Democracy Front” will offer us more favorable conditions to organize on than a win by fascist forces—even as it will undeniably offer up new challenges, as the post-election experience of the NFP also shows. But they will be better challenges than the ones that face us under an emboldened right-authoritarian regime.

Perhaps that’s a good way of putting it. Under challenging conditions, we are fighting for better, bolder challenges. Challenges that offer us greater openings—if, like the New Popular Front, we have the audacity and acumen to take them. So let’s get to work.

Bennett Carpenter (they/them) is a queer Southern organizer, trainer and movement strategist. A member of the National Executive Committee of Liberation Road, they have extensive experience in labor, community and electoral organizing. Bennett spent several years living in France and the Netherlands and maintains strong ties with socialists there. They now live in small-town eastern North Carolina with their husband Attila.

While the US is also technically a republic, we more typically refer to our government as a democracy, so a good translation might be something like the “Democratic Front”—or perhaps better, the “Pro-Democracy Front” to distinguish this from a narrow focus on the Democratic Party.

While we can debate their significance and durability, there is no question that the Biden administration has embraced neo-Keynesian policies. Meanwhile the centrist wing has continued to move left on many social issues (but to the right on immigration). Only on foreign policy do they represent real continuity with the “governing consensus” of the 1990s, a sign of how deeply entrenched the foreign policy consensus remains across both the center and the right. (Where, despite the myth of MAGA isolationism, the MAGA right both represents both continuity with and intensification of US militarism and neo-imperialism.)

Good job, Bennett

Super description and analysis, Bennett.