Manufactured Dreams

Trump's promises to workers are a pipe dream. But the Left needs to develop our working-class narrative.

By Jeff Crosby

Introduction

The united front to defeat Trump and the resurgent New Confederacy requires all hands on deck, the broadest possible forces. But at this moment, to build an alternative to the MAGA fascist movement, the heart of the battle is a fight to win the working class, with its own organizations and narrative.

We fight over material things, battle after battle. Then there is the fight over ideas, the fight to create a hegemonic narrative of our own. Our story. In this battle too, the wealthiest have had the advantage. In this election and in the next decade or two, a major part of the fight will be over the place and history of the manufacturing decline over the last 50 years.

The material and social impact of free trade and neoliberalism still haunts the dreams of millions of working-class people who lived through the decline of manufacturing in the US. Who will interpret these dreams, created in steel and hard work, realities and myths, truth and lies? The memories of good jobs lost, the dreams of good jobs in the future?

Working at GE as the Buildings Fall

I punched in as a grinder at General Electric in Lynn, Massachusetts, in February of 1979. Margaret Thatcher was elected in June, Ronald Reagan in November. In the 30 years that followed, GE was among the top two or three corporations by value in the world. Fortune magazine named CEO Jack Welch the “Manager of the Century,” but GE workers called him “Neutron Jack,” after the neutron bomb that could destroy human beings while keeping buildings intact. Local 201, a great union since its birth in 1933, continued the fight for our members’ livelihoods.

Then in 1993 came the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which eliminated tariffs on trade among Canada, Mexico, and the United States, allowing for the unfettered movement of capital and foreign investment. NAFTA was the single biggest culprit of deindustrialization, increased income inequality, weakened unions, and shorter life span for working class people. It has come to signify all the free trade agreements that followed, part of the neoliberal trifecta of deregulation, privatization, and free-trade—and its ideological running mate, dog-eat-dog individualism.

After NAFTA, every union negotiation with GE, local and national, was carried out under the real threat of plant shutdowns and work transfers to Mexico. This had a huge impact, far beyond the jobs that were actually moved. We survived remarkably well: Today, 1,300 members build aircraft engines in Lynn in what is a “good job.” But still: we lost our defined benefit pension, accepted an extended pay progression to get to the top scale (reduced in subsequent negotiations), and saw our medical plan deteriorate. So I got an up close and personal look at the systematic destruction of manufacturing.

The city of Lynn, too, was hollowed out, just like US corporations were. Its main street was abandoned, crime rose, pay dropped or stagnated, and every health measurement declined.

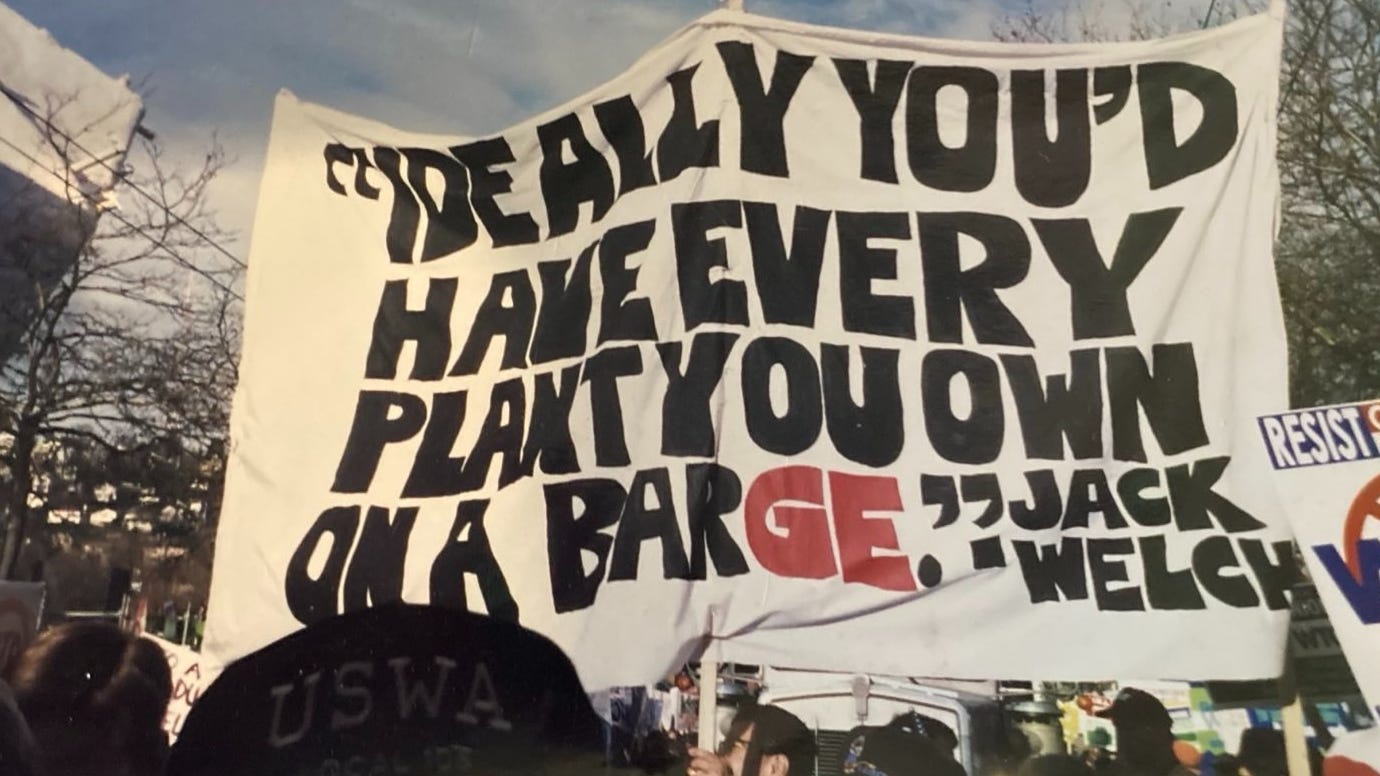

There is more than one reason for that, of course. The shopping malls sucked the life out of Lynn’s small businesses in the 1960s, and all seven theaters closed. A planned interstate highway leveled a multiracial neighborhood in the center of town known as the Brickyard, before construction was blocked by community resistance. Nevertheless, the city was fairly healthy until the early 1980s. Then the GE jobs began to leave: to Mexico, to China, to Hungary, to India, everywhere. Jack Welch bragged that he would “put every plant on a barge” if he could. If a community or a union got a toehold of security against the corporation, GE would just move to greener pastures with more exploitable workers, wherever that might be. Capital is mobile, workers not so much. Lynn GE was a microcosm of the national story writ large.

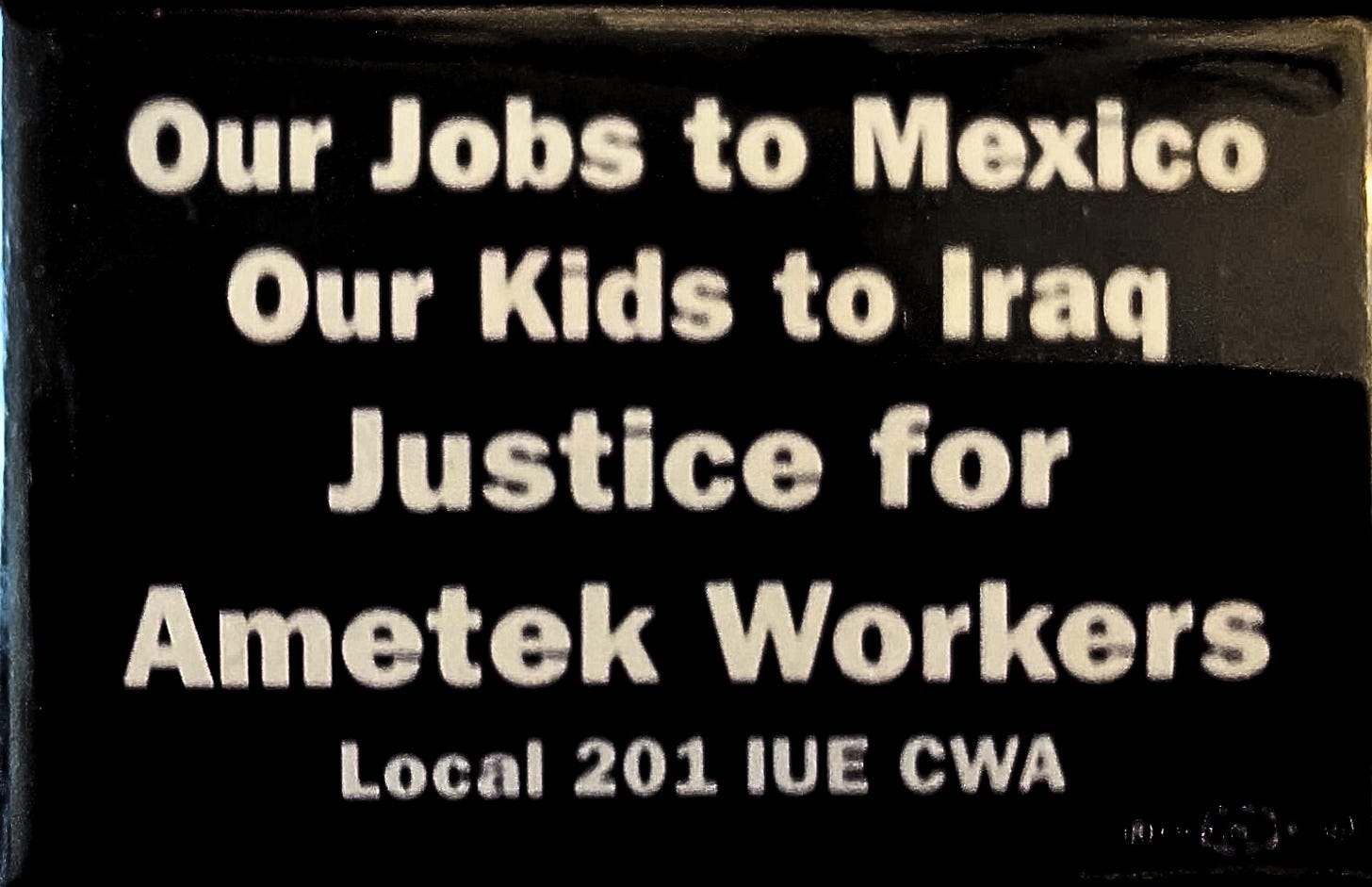

GE called a conference of aviation subcontractors in McCallum, Texas, to tell them they must move to Mexico: “it’s not a question of if, but when.” It did not go down well with the subcontractors like Ametek Aerospace, some of whom could not or did not want to move, and were also represented by Local 201. A disgruntled manager left notes from the meeting on the workbench of a union steward, which we in turn fed to exposés that appeared in Business Week and Bloomberg. GE explained the wages were much lower for everyone, from machinists to engineers, and health and safety protections were weaker. A foreign company could pick the union they wanted or chose to have no union. GE promised to help finance the move—otherwise, the subcontractors “will not do business with GE.”

We fought the loss of our jobs while countering racism and nationalism. We sent members to look at the maquiladoras (factories with US parent companies) across the Rio Grande where our work landed. We knew that when subsidized US corn flooded the Mexican market, impoverished subsistence farmers would in turn flood the border. We hosted struggling Mexican independent unions, and others from El Salvador. We marched against the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Seattle and the Free Trade Area of the Americas treaty in Quebec, against the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank in Washington, DC, and Miami. We got tear-gassed in a half-dozen cities. We joined delegations to Colombia to support unions there against US military aid to their murderous government and oppose the Colombian free trade agreement. We sponsored a Colombian trade unionist under death threat whom the AFL-CIO brought to the US.

We bargained hard and for real, using what remaining political and production leverage we had. As one Local 201 leader put it, “They knew that if they closed us, the pain would be shared.” Protests, rallies, strike threats, smaller job actions – everything we had.

The 1999 Seattle demonstrations—you might remember “Teamsters and Turtles, Together at Last”—represented a moment when anything seemed possible.But 9/11 ground the movement to a halt. The best we could do was build “Fortress 201,” stop the bleeding when we could, and land some blows as we survived to fight again.

For this, most elected officials, economists, journalists, and pundits treated us as neanderthals and racists who did not want to share our bounty with Mexican workers making $6 a day. Skilled jobs, they told us, would replace our “unskilled” jobs, as though cutting titanium to plus or minus a few ten thousandths of an inch was nothing. As though the engineering and management jobs would not cross those same borders. As though we could all be “retrained” in our 50s to be computer programmers. As though anyone could be expected to calmly watch their livelihoods and communities systematically destroyed.

Republicans and Democrats

Neoliberalism and free trade were a bipartisan project: Ronald Reagan originally proposed NAFTA; Bush negotiated and signed it. But it took Clinton’s influence with Democrats to get it through Congress. We had a better chance of stopping free trade agreements if a Republican was president. An unrepentant Clinton and the Democrats took the blame, even though a majority of Democratic congressmen voted against the treaty.

We never expected anything from the Republicans, but the arrogance was bipartisan. We organized to win a vote at the Massachusetts Democratic Party convention to oppose NAFTA. We were treated with contempt by the lawyers and other professionals who dominated the meeting. Half the Democratic congressmen from our state voted for NAFTA anyway. Our local never attended another state Democratic function and never gave another nickel to the Democratic Party.

President Obama promised to renegotiate NAFTA when he campaigned in post-industrial Ohio in 2008. He lied. Just before the ‘Blue Wall’ crumbled and Hilary Clinton lost in 2016, Democratic Senate leader Chuck Schumer dismissed us again: “For every blue-collar Democrat we lose in western Pennsylvania, we will pick up two moderate Republicans in the suburbs in Philadelphia, and you can repeat that in Ohio and Illinois and Wisconsin.”

So for us factory floor survivors of neoliberalism—roadkill on the highway to the “New Economy”—it’s head-spinning to hear both political parties today claim to champion manufacturing. Everyone is bragging that they are “bringing back manufacturing.”

Suddenly we’re heroes again?

Reality, Intersections, and National Myths

To understand this reversal, we need to understand the role, both material and mythological, of manufacturing in our national narrative.

Fueled by coal and steel, the US was a growing manufacturing power before the last world war. Post WWII, the US stood atop the world economy, extending its influence over the receding European powers from French Indochina to the Dutch West Indies to the remnants of the British empire. The latter became junior partners in the competition with the Soviet Union. By the 1960s, the US produced 50 percent of world manufacturing output, and General Motors alone produced one-tenth of US manufacturing wealth.

As a young man, I often made the road trip from Wisconsin to Massachusetts and back. At night the smoke and flames from the mills of Hammond and Gary, Indiana, and Chicago’s South Side seemed to stretch for a hundred miles. They spoke of men at work. They spoke of power.

GE expanded on its earlier growth with massive government investment during and after the war. The government built a plant in Everett, Massachusetts, represented by Local 201, and gave it to GE for a dollar. Responding to the 1946 strike which shut every plant GE had in the Northeast, the company built a network of plants along the Ohio River and further South, often in small towns where they were the largest employer.

The social impact of US manufacturing dominance was arguably more powerful and long-lasting than even the material impact. It is hard for those born after the 1960s to imagine this. Real wages for all workers rose at about 2 percent a year during the 1950s, unmatched before or since. Homeownership, nurtured by government tax incentives and the GI bill, ballooned. Union density peaked in 1954 at 34 percent of those legally allowed to organize, forcing nonunion employers to keep only a step or two behind.

But it was more than that. Manufacturing was prominent in popular culture and intellectual life. Hank Williams was a shipfitter in Mobile and Portland, Oregon. Chester Hines worked in a factory before writing Cotton Comes to Harlem, and telling the story of Black factory life and union organizing in Lonely Crusade. Walter Mosely’s street detective Easy Rawlins, one of my favorite fictional characters, lost his job in an aviation factory in LA after joining the Southwestern stream of the Great Migration. Marilyn Monroe worked in a factory when she was still Norma Jean.

Popular narratives honored the working class and gave us a sense of power and purpose—but also perpetuated nationalism and gender hierarchy. Good factory jobs had allowed “a man to support his family.” A man could fulfill his “God-given role” as provider, and as both civic and family leader. Women “didn’t have to work,” as though working-class women had not always worked—from slavery times to sharecropping to Lynn’s shoe industry and the WWII defense factories and farming, and in both paid and unpaid domestic labor.

Nationalist triumphalism had a big place in all this too. Miners in West Virginia and steel workers in Pittsburgh and assemblers in Detroit and Los Angeles and Lynn won the war. We wrote the story of a triumphant America: we dominated the world, kept the peace, defeated fascism, and kept Stalin at bay with our industrial might. Rosie the Riveter had her moment (but only a moment) in GE Lynn and WWII factories everywhere. The B-17s my father flew over Germany out of England were built by factory workers in Seattle and Long Beach and Burbank, California, during the greatest industrial mobilization in our history. The super-charger for the engines on his Flying Fortress was produced by workers in Local 201 35 years before I punched in. GE workers in Lynn also built the first jet engine.

Now skip forward a few decades. The sons and some daughters of the WWII and Korean vets went to work in Lynn in the 1970s and 1980s. It was a factory town. I know families who have worked in the same plant for three and even five generations.

Manufacturing jobs were what people did or hoped to do. But these hopes crumbled under the weight of deindustrialization and bipartisan neoliberal policies. There were layoffs, buildings were torn down, everyone was afraid the plant would close, and GE brought in vendors from distant continents so we could show them how to do our jobs. (Needless to say, we refused.)

Things fell apart, and our culture reflected that. Perhaps Bruce Springsteen’s most powerful words are found in the song “Youngstown”:

“Well my Daddy come on the Ohio works

When he comes home from WWII

Now the yard’s just scrap and rubble

He said “Them big boys did what Hitler couldn’t do.

These mills they build the tanks and bombs

That won this country’s wars

We sent our sons to Korea and Vietnam

Now we wonder what they were fighting for…

Now sir you tell me the world’s changed

Once I made you rich enough

Rich enough to forget my name.”

Trump: Political Gangrene

As opportunities shrank, the patriarchal and nationalist mythology—and the rage—grew. In this context, Trump pulled a fast one. He did not run as a Republican; he ran as a MAGA candidate against both the Republican and Democratic party—in other words, against the “elites” who brought us free trade and the destruction of manufacturing and the nationalist and patriarchal myths that came with it. He told the Republican National Convention this year, as though responding directly to Springsteen’s complaint: “To all of the forgotten men and women who have been neglected, abandoned, and left behind, you will be forgotten no longer.”

The appeal to patriarchal myths resurfaced again, as Republican vice-presidential nominee JD Vance imagines a world where once again women’s place is raising babies, their honored and only proper role, the female prison pedestal. He’s reprising a battle fought in Lynn in the 1870s, when clergy wielded the “Cult of True Womanhood” against Irish immigrant women who worked dangerously and “promiscuously” close to men in the shoe factories. Unnerved by cultural changes? “I will protect you,” Trump promises.

Trump also manages to address both the fatigue of working-class Americans with the “endless wars” and the sense of humiliation from US defeats from Vietnam and Afghanistan. These are intertwined with the end of US industrial domination of the world, like Nazis mourning Germany’s defeat and humiliation after World War I.

Trump infected these open wounds—material, spiritual, and mythical—like gangrene. In 2016 he landed in small towns where the Democrats never ventured. In Iowa alone he held rallies in Waterloo, Dubuque, Marshalltown, Clinton, and Oskaloosa (where my father grew up), county seats and small towns. He closed his 2024 primary campaign in Rome, Georgia, the largest city in Marjorie Taylor Greene’s district. This was once the site of a powerful GE factory union local. Now closed.

Trump spews lies about the manufacturing jobs he created during his presidency. During his presidency manufacturing jobs dropped by 200,000. But desperate, angry people sometimes believed his lies. Retired union miners in West Virginia told me about all the new steel mills in Cleveland and coal mines that Trump had opened. Miners hate the bosses more than any workers I have ever met, but they felt betrayed and wanted to believe an anti-establishment billionaire fraud would turn the tide.

And Trump builds on the history of white supremacy in our country: the foundations of slavery and Jim Crow, the reaction to the Second Reconstruction in the 1970s and mass incarceration, and now the scourge of neoliberalism, which hit Black workers hardest.

Despite Trump’s virulent racism, it should not be surprising that some Black and brown workers support him. As part of the multinational working class, some react to the same things that white workers do: job loss, and patriarchal and nationalist myths. In a visit to the Rio Grande border to try to organize GE workers there, I heard complaints from Mexican American and Chicano workers about their jobs moving across the border to a GE plant just a few miles away. And the Mexican plant employed not just workers of Mexican descent, but family members of workers on the US side.

Our Own Narrative

Millions of workers in the US continue to make things—and to fight for a better life for themselves, their families, their communities, and their class. Now in 2024, Harris and Walz have a chance to reverse the Democratic losses, or at least reduce them, in rural working-class towns. They can point to actual manufacturing investments in both red and blue states; 739,000 new manufacturing jobs were added during the Biden administration, partly through corporate retreats from China and the stimulation of the Inflation Reduction Act and Build Back Better. Neither Harris nor Walz have a pro-NAFTA or free trade history. They are campaigning outside the big cities. Walz is from a Nebraska town even smaller than the small towns where my parents grew up in Iowa and Missouri.

The worst part of the 2024 presidential campaign is that a bloodsucker like Trump has swindled any working-class people at all. He was born a millionaire and has never done a real day’s work. He thinks losing other people’s money is a job. He claims he wants to deport millions of undocumented workers, framed in the most racist way imaginable, worse even than George Wallace’s segregationist campaign in 1968. Whatever the reasoning, to look away from virulent white supremacy is a stain on the soul of workers and the working class.

I’m all for the politics of joy if it can stave off fascism. If Harris and Walz win, it will be easier to vote, women will have access to reproductive health care, unions will be able to organize, and we will not face mass deportation of millions of our working-class people. This is more favorable terrain for our peoples. The various strains of abstentionism—“Wait till 2028 and we’ll run our own candidate,” or “Focus on down-ballot races,” or “build our movement,” or “No votes for genocide,”—reflect a useless purism that is not only wrong, is it dangerous. Some think of abstentionism as a moral response to Trump. On the contrary, it is immoral to choose a losing strategy, from which all of us will suffer.

But to move beyond this, we will have to write our own narrative, an anticapitalist, internationalist narrative, purged of racism, patriarchy, and nationalism. A narrative that identifies the actual enemy, the multinational corporations who today write the rules. Targeted investment in the areas that need it the most. Massive job training and education investment to keep up with changing technology and a multilingual country. Trade agreements that expand union and human rights, and that raise wages. A narrative that will have to be repeated again and again, until it becomes common sense.

Our own manufacturing dreams, not manufactured dreams.

Jeff Crosby worked at General Electric in Lynn, Massachusetts, for 33 years, and was president of his local union and the area Labor Council. He offers this perspective as a worker, union leader, and socialist.

A powerful argument. In the last instance, production matters. Neoliberalism is really a one-sided class war (see David Harvey, "A Brief History of Neoliberalism"). By offshoring production, our ruling class imposed a harsh discipline on American workers, reducing Americans to consumers in a financialized economy that prioritized profits, hollowing out our cities and gutting the industrial core of the USA.

As a result of this spatial fix for capital (D. Harvey), China is now home to more manufacturing capacity than the US, EU, Japan, and the ROK combined. About 30-35% of all manufactured goods come from China and the Asian productive ecosystem that extends into Africa. The collective West is the past, Asia is the present, and Africa is the future.

Another consequence of neoliberal globalization was the displacement of peasants off the land and into megacities of the Global South, creating a global proletariat in a "Planet of Slums" as the late great Mike Davis put it. Those former subsistence farmers and small commodity producers now must sell their labor power within a governance system framed by dependency and neo-colonialism. This has had a dramatic effect on Africa and cities of the Global South as AbdouMaliq Simone notes in the "City Yet to Come".

Despite the hope of "making America great again" the genie is out of the bottle and no amount of re-shoring,blustering, and bombing can undo what was done when the process was global as Peter Dicken notes in "Global Shift: Mapping the Changing Contours of the World Economy". Electing Harris is no panacea, but a necessary strategic move to shape the terrain in what promises to be a tumultuous period of change "unseen in a century" (Xi Jingping).

The three day BRICS meeting occurring right now in Kazan might mark a turning point in the relationship between the formerly colonized and former colonizers, and the beginnings of a pluralistic system that could compliment and eventually supercede the rules based order made in Washington, NYC, Paris, Brussels, Tokyo, and London.

Excellent. It's the story of my hometown, Aliquippa, in Western PA. Nearly every word of it. Going forward, it's worth making use of the resources of the Federation for a Manufacturing Renaissance, chaired by Dan Swinney in Chicago, with many U.S. allies and connected to the Mondragon Coops in the Basque Country of Spain as well.