Global Capital's Financial Shells

Offshore tax havens, and what they tell us about what is really going on

In 2022, the Netherlands ranked number two in the world for foreign direct investments (FDI). Over $3.2 trillion in capital flowed out of the small country into investments all around the world, outranking everybody but the U.S.

Moreover, in 2022 the Netherlands received more incoming FDI from the U.S. than any country other than the UK, some $944 billion. In fact, between 2012 and 2017 it ranked between number one and four each year for incoming foreign direct investments–a better record than China’s.

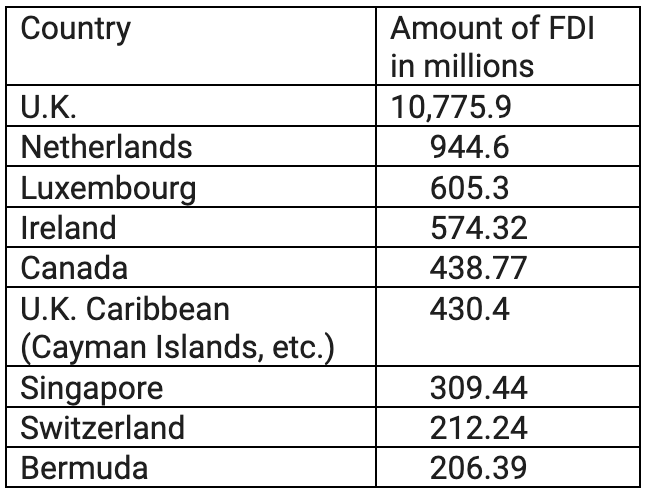

Besides the Netherlands, where would you assume most U.S. capital is invested? Maybe China, Mexico, Brazil, Germany, or Saudi Arabia? You would be wrong on all accounts. Here are the top nine countries that received FDI outflows from the U.S. in 2022:

So, what is going on and what does this tell us about global capitalism? Most of this money is not going into these countries to acquire or build factories. It comprises capital flows into financial shells and firms that flow out into other investments. This money also includes profits that sit in financial institutions to avoid taxes.

This goes back to my first column on offshore finance known as non-resident capital–that constructed world for transnational capital, with its own rules operating in offshore financial centers (OFC). These centers capture the largest percentage of offshore capital stocks and flows globally. Some, like the Cayman Islands, attract capital mainly from investment funds and banks, while the Netherlands and Luxembourg act as gateways for transnational corporations. Hong Kong gives access to China. The system functions as an integrated offshore world in which global financial institutions and a handful of powerful law and accounting firms keep the legal mechanisms, treaties, and data operating.

Marx and Engels made the point in the Communist Manifesto that capitalism was already a world system, transforming national markets in new revolutionary ways. This process has never stopped. Capitalism has increasingly become more global and more integrated. The era we know as globalization is just the current stage, but an important one in transforming the relations of production and the functions of national states and producing a transnational capitalist class.

National markets and legal restrictions still were dominant until the 1980s. But such territorial enclosure limited global capital mobility and the growth of corporations. One of the most basic instinctual drives of capital is to constantly expand. It never stands still, but needs to be reinvested and multiply itself. That creates the competitive drive that results in success or failure. If you don’t expand, your competition will, and eventually drive you into bankruptcy.

The Keynesian social system built on an international system of national competition faced a fundamental crisis of profitability in the late 1970s. Too much national capital went to the working class, and national borders were limiting expansion. The hegemonic bloc that came out of the Great Depression and World War II was overturned. Instead, we got neoliberalism and globalization, with the most powerful wing of the bourgeoisie transforming from its national roots into a transnational class based in integration of global production and cross-border financial flows.

One result was the creation of offshore financial centers encased in an entire legal system, constructed on a global scale that freed capital from national restrictions. This was a world apart from national oversight, supposedly protected from popular rebellions. But global capitalism created such growing inequalities that protests and anger built and exploded. In both left and right political directions, which is where we are today.

In the next column we’ll explore some of the complex relationships between state sovereignty and the rule of global capital–a contradiction becoming ever more tense and dangerous.

Jerry Harris is the national secretary of the Global Studies Association of North America, and on the international board of the Network for Critical Studies of Global Capitalism. His articles have often appeared in Race & Class (London), Science & Society (New York) and International Critical Thought (Beijing). His last book was Global Capitalism and the Crisis of Democracy. His work has been translated to Chinese, Spanish, Portuguese, German, Czech, and Slovak.