Announcing The New Liberator

Fighting for a Third Reconstruction worthy of our ancestors and our future

Liberation Road’s newsletter is moving forward with a new name. The New Liberator is a pledge to the revolutionary ancestors whose struggles came before us. It is a promise to those in the future who will look back on the struggles we waged. And it is our offering to all those in the present committed to revolutionary strategy in these bleakly counter-revolutionary times.

With this name change, we’ve made some tweaks to our newsletter layout and graphic design. Moving forward, we’re excited to try out some other changes as well—including experimenting with video formats and finding ways to engage our subscribers in more active real-time dialogue. What won’t change is our commitment to provide sharp takes, sober analysis, and strategic insights posted online and sent straight to your inbox.

Do you have other suggestions for how we should switch things up—or what you’d like to see us keep doing? Please post them in the comments below! Or email us at info@liberationroad.org.

Liberatory Legacies

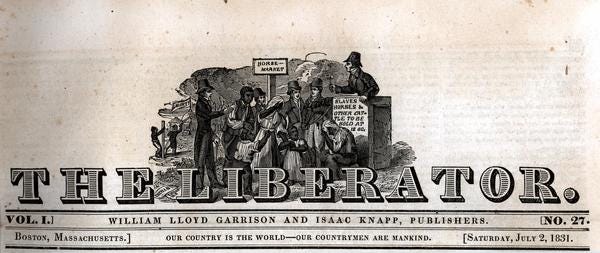

In 1831 William Lloyd Garrison launched The Liberator, a weekly paper that for a generation published uncompromising positions against the Confederate slave power and its revanchist white patriarchal regime. Over the course of its run, The Liberator played a powerful role in the abolitionist battle for the common sense, moving large numbers of people to the side of emancipation. The paper often reported on fugitive slave cases and updated its mostly Black readership on the work of mass anti-slavery organizations like the New England Freedom Association and the Boston Vigilance Committee. The Liberator also advocated for women’s suffrage, rights, and equality, publishing Sarah Grimké’s “Letters on the Province of Woman” and promoting women’s political leadership within the abolitionist movement.

One of the paper’s famous early contributors was Frederick Douglass, who ultimately split with William Lloyd Garrison over disagreement about whether the Constitution was a pro-slavery or anti-slavery document. This dispute was less about legal analysis than abolitionist strategy. Garrison believed the disproportional representation of the US Senate and the Three-Fifths Compromise granted slave states a stranglehold on political power that rendered efforts to reform the system from within impossible. As a result, he argued that abolitionists should agitate for electoral and political abstention and, ultimately, northern secession. Douglass came to believe that this position, while theoretically radical, led to political quietism and abstention from practical mass struggle. He came to believe that Black people must fight for freedom using all the tools available to them—including a Constitution which, while originating in slavery, could be turned against the will of its founders.

In the end, events proved them both half right. It took disunion and secession to bring about the end of slavery, as Garrison had predicted. Yet secession occurred as a result of the election of Abraham Lincoln through the exact kind of pragmatic political activity that Douglass had come to espouse. And this process culminated in the radical transformation of the US Constitution through the Reconstruction Amendments which abolished slavery, established birthright citizenship, and granted Black people the right to vote. Declaring that “the object for which The Liberator was commenced—the extermination of chattel slavery—has been gloriously consummated,” The Liberator announced its last issue shortly after the ratification of the 13th Amendment in December 1865.

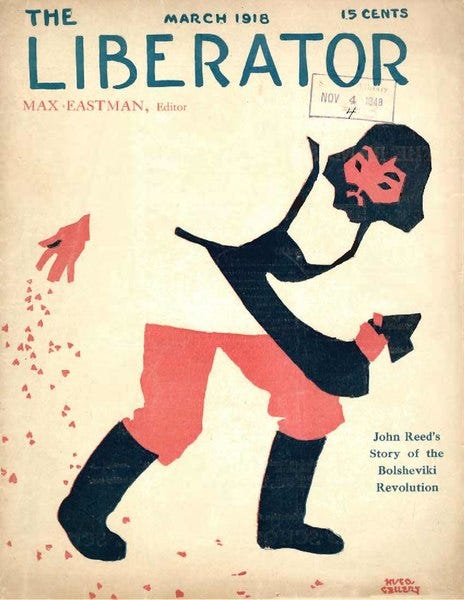

A half-century later, the newspaper’s name reemerged as the title of a new monthly magazine edited by socialist feminist Crystal Eastman and her brother Max. Launched in 1918, The Liberator was founded to continue the work of an earlier journal, The Masses, which the Postmaster General had shut down under the Espionage Act because of its anti-war and anti-imperialist stance. Graphically innovative and politically non-sectarian, The Liberator was an important forum for early American Marxism. The magazine featured writers from all sectors of the fledgling socialist movement, from gradualist to revolutionary. But its own editorial viewpoint was unique in carving out a position somewhere between these two poles—much more radical than mainstream progressive publications like The New Republic, but much more open to pragmatic Progressive Era reforms than other radical magazines of the time period, like Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth.

Like its predecessor, The Liberator advocated for women’s suffrage and promoted concrete reforms such as birth control, treating gender liberation as a crucial terrain of struggle at a time when other sections of the radical left dismissed this as a distraction from the class struggle. It also provided in-depth analysis of all sectors of the labor movement, and was notable for its detailed international coverage, publishing ongoing updates on the situation in the new Soviet Union from wartime correspondent and Communist Labor Party founder John Reed. In the 1920s, the paper was taken over by the nascent American Communist Party, which ultimately merged it into the New Masses, one of the principal organs of the American left from 1926 to 1948, when it shuttered amid the onset of McCarthyism.

What’s in a name?

The New Liberator aspires to live up to these legacies with deep humility and fierce urgency. We stand on the shoulders of revolutionary giants, and, in this heightened moment of danger, it is our duty to carry forward their struggle for socialism, anti-imperialism, and abolition democracy.

Today the New Confederacy is marching towards fascist autocracy. Rather than the formal secession of its predecessor, this New Confederacy is achieving a de facto strategy of neo-secession from the decaying liberal bourgeois democracy of this country, creating a reactionary republic amidst its wreckage. This New Confederacy has pursued a decades-long strategy to capture the vast legal power of the judiciary system, transforming it into the primary staging ground for a full-on assault on the Reconstruction Amendments of the Constitution—the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments—and the Civil Rights Amendments, the 23rd, 24th, and 26th. This New Confederacy has ballooned the funding and scope of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and has given it the power and means to be our own American Gestapo, building a system of concentration camps to launch a campaign of mass ethnic cleansing. This New Confederacy has launched an all-out assault on the rights of trans and cis women and all gender-oppressed people, criminalizing abortion and attempting to eradicate trans existence entirely. This New Confederacy is dismantling the welfare state, attempting to defeat and destroy mass movements and the socialist left, and orchestrating the largest upward transfer of wealth in modern US history. The New Confederacy is underwriting genocide in Gaza, building a new fascist international with other right-wing autocrats around the globe, and intensifying conflict with China, heightening the risks of world war.

In this perilous period, we root ourselves in the legacy of all those liberators and Liberators who dared to dream of abolition democracy in the very midst of the Confederacy, to advance socialist strategy from the heart of capitalist empire, and to promote international solidarity against war and imperialism. We are inspired by the ways in which both Garrison’s and Eastman’s Liberator linked struggles around abolitionism and socialism to feminist struggle, resisting divide-and-conquer efforts and insisting on the intertwinement of race, class, and gender oppression. We invoke both Garrison’s radical clarity on the structural racism of the US political system and Douglass’s strategic clarity on the need to struggle within and against systems, even or especially when we know they were not built for us. Like Eastman’s Liberator, we hope to provide a space for robust debate on the left that features a range of opinions, but promotes a clear-eyed inside/outside strategy that balances radical vision and practical action. We commit to this newsletter to strengthen our collective clarity on the US Left because we know it is our duty, not only to struggle, but to win.

Aaron Jamal is an organizer in North Carolina and is committed to the socialist transformation of the United States. Aaron writes regularly on his Substack, Black Unbound.

Bennett Carpenter (they/them) is a queer Southern organizer, trainer and movement strategist. They are a member of the National Executive Committee of Liberation Road.

Good effort there. I especially would appreciate being ablate easily read others comments and letters.